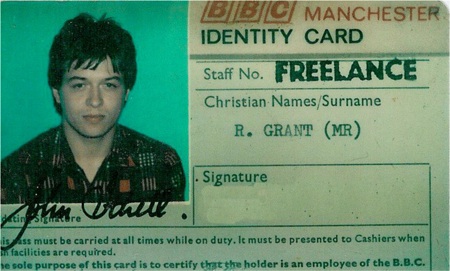

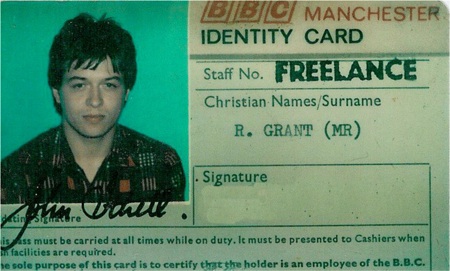

Rob’s BBC ID card

Rob’s BBC ID card